Do Pictures Change Patient Behaviors?

The Limits of Fear in Medicine

When I was a younger physician, I believed that patients were intellectually and emotionally responsive to data the same way that I was. If I showed them the problem - a blocked artery or one full of atherosclerotic plaque - they would be motivated to make healthier choices. But after several years studying how physiologic information affects patient and physician behaviors, I learned a humbling truth: doctors tend to respond to data; patients … not so much. Showing patients pictures of disease may create fear, shift risk perception, and change their stated intentions, but long-term behavior change is rarely that simple.

Why Might Personalized Health Information Help Patients Change?

Personalized information is appealing because we assume it counteracts feelings of invulnerability or lack of concern, making the risks feel personal rather than abstract. Psychologically, showing a patient an abnormality in their carotid or coronary artery raises threat perception and fear, which we hope will motivate change (1). The pop psychologist in all of us believes this will push a patient or a loved one to “get with the program” or “take his health seriously.” I have heard countless spouses tell me, “If you could just scare him, he’ll change.”

It makes sense, right? We all know the idea of the “teachable moment” - that after a life-threatening event, many patients become more willing to change their lifestyle. And after a coronary angiogram, we often show patients pictures of their arteries to “get their attention” and underscore the seriousness of what they had and what we did. But in 2025, we should not lean on intuition when so much evidence shows that fear, by itself, is a poor strategy for changing behavior.

My Patient

I once saw a 49-year-old my in my preventive cardiology clinic who had a terrible family history of heart disease. His father had a heart attack on his 50th birthday and died nine months later of progressive heart failure. Several relatives on his father’s side had premature coronary artery disease, including cases of sudden cardiac death. He was a nice, charming, but stubborn man who was interpersonally engaging but clearly didn’t want to be in my clinic. He was 6 feet tall and weighed 230 pounds (body-mass index 31.1 kg/m²). He exercised 5-6 days a week for 30-45 minutes, but became defensive whenever we talked about his weight or his heart disease risk factors. “I’ve always been a big boy,” he told me. “I’ve always had a big appetite.”

His blood pressure was 148/92 mmHg. He was not taking any medications. His cholesterol profile was concerning: total cholesterol 246 mg/dL, HDL-C 32 mg/dL, triglycerides 210 mg/dL, and LDL-C 172 mg/dL. He had been prescribed statins at least three times previously, but never filled the prescription or took them beyond a couple of months.

I told myself, “Maybe seeing his atherosclerosis will motivate him to take a statin and change his lifestyle.” It would motivate me, for sure, so I ordered a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score

How does Personalized Biomarker Feedback Actually Perform as a Motivational Tool?

The best research on this question comes from the smoking-cessation literature (1). For decades, investigators tested whether giving smokers personalized feedback about smoking-induced physiologic damage - chest x-rays, pulmonary-function tests, exhaled carbon monoxide levels, even ultrasound images of carotid plaque - would increase motivation to quit. The logic is intuitive: if patients can see the consequences, the threat should feel more real and produce fear. Fear should lead to reflection, which should lead to action. It’s the same logic clinicians use when they say “Seeing this will make her take it seriously.” It makes perfect sense. But as I learned from my research and what others have shown repeatedly, what makes sense to doctors does not necessarily change patient behavior.

What the Cardiovascular Disease Imaging Studies Actually Show

One of the earliest efforts to test whether CAC screening could change behavior was the PACC project, a six-year follow-up of 1,640 men (2). Those with detectable CAC were more likely to receive statins and aspirin. Observational studies have consistently shown the same pattern: patients with high CAC scores are more likely to start medications, report intentions to change their diet or exercise, and show slightly better statin adherence.

I found similar results in my own work (3,4). In the OPACA study of office-based carotid ultrasound, identifying increased carotid wall thickness or plaque led physicians to prescribe more aspirin and lipid-lowering therapy, and patients reported greater motivation to improve their lifestyle. What surprised us was that even patients with completely normal ultrasounds reported increased intentions to exercise and eat better. Simply undergoing the test seemed to activate short-term intention. We confirmed this in a larger follow-up study of 355 primary care patients. Abnormal findings again prompted more prescriptions and stricter risk-factor targets. Immediately after screening, patients endorsed numerous lifestyle intentions, but within 30 days almost all of those intentions had evaporated, and there were no changes in exercise or weight. Awareness increased, but action did not.

Given these results, it is not surprising that randomized trials of imaging interventions failed to show meaningful behavior changes. In the CAROSS study, 536 smokers were randomized to see their carotid ultrasound images or not (5). All received counseling and nicotine replacement. After 12 months, cessation rates were identical, and plaque findings had no impact on quitting or other risk factors. The PACC randomized trial also found no effect: CAC scoring added nothing, and the only group that improved was the one receiving intensive case management (6).

Even the EISNER trial, the largest randomized study of CAC imaging (2,137 adults), showed only marginal effects: systolic blood pressure was 2 mmHg and LDL cholesterol 6 mg/dL lower in the CAC group, differences driven by more aggressive prescribing, not better adherence or lifestyle changes (7). Diet, exercise, and weight did not change at all. A smaller RCT in postmenopausal women showed the same pattern; if anything, the control group improved more (8). EISNER remains the most rigorous trial conducted, and more than a decade later, no study has contradicted its findings. If imaging meaningfully improved lifestyle, we would have seen it by now.

Understanding the Psychological Effects of Personal Information on Behavior

The psychological framework most relevant to why personalized health information might work is the Extended Parallel Process Model. In this model, people engage in protective behaviors only when two conditions are met: they perceive themselves to be at genuine risk (threat appraisal) and they believe they can do something effective to reduce that risk (efficacy appraisal). Threat appraisal involves judging how severe the danger is and how personally susceptible one feels. Efficacy appraisal involves assessing both one’s ability to carry out the recommended behavior (self-efficacy) and whether that behavior will meaningfully reduce the threat (response efficacy).

When both appraisals are high, people are more likely to accept the message and moving toward solutions, such as quitting smoking (“danger control”) But when threat is high and efficacy is low, fear often produces the opposite response: avoidance, denial, or cognitive strategies that minimize the message. This “fear control” pathway leads patients to withdraw from the very information intended to help them. Personalized biomarker feedback is thought to work best when it makes the threat feel real and immediate, reducing the disengagement beliefs that allow patients to distance themselves from risk. But without a strong sense of efficacy, fear simply shuts people down.

Putting It Together

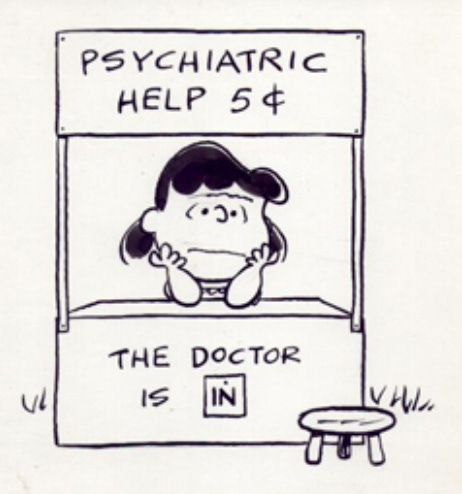

Physiologic information can increase awareness and influence prescribing, but it does not help patients achieve meaningful prevention targets. Sure, we all know of a few patients who had a CAC scan, “got religion,” and transformed their lifestyle. That is wonderful, but it is also the exception, and those stories stick with us because they confirm what we want to believe. Most behavior change is far more complex, and problems rooted in habit, personality, and addiction rarely yield to a single image or test. Sustained change comes from relationship-centered work – motivational interviewing, coaching, communication skills, and follow-up – not from the picture itself.

The EuroAction study demonstrates this point (9). In this trial, 3,088 patients with coronary artery disease were randomized to usual care or a nurse-coordinated, multidisciplinary, family-based intervention delivered by a nurse, dietitian, and exercise physiologist. Participants attended eight weekly sessions focused on lifestyle skills, communication, goal-setting, and family engagement. The results were substantial: the intervention group improved their diet, blood pressure, lipid profiles, and smoking cessation far more than those in usual care.

The first step is caring, not testing. As Dr. Patrick O’Malley wrote about the PACC study (10):

“A picture may be worth a thousand words, but relationships move mountains when it comes to transformative personal change,”

Back to the Case

My patient underwent the CAC scan. His score was markedly elevated at 2,186, with extensive calcification in the proximal LAD, ramus, and circumflex coronary arteries. After I informed him of the results, he missed his next three clinic appointments, did not return our phone calls, and never responded to a follow-up letter. Ultimately, he was lost to follow-up.

I messed that case up. Back then, I placed too much weight on the images and was impatient. I ordered a test rather than spending more time building trust and supporting his self-efficacy. I hope he eventually sought care and is doing well.

References:

Shahab L, et al. The motivational impact of showing smokers with vascular disease images of their arteries: a pilot study. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12:275–83. doi: 10.1348/135910706X109684.

Taylor AJ, et al. Community-based provision of statin and aspirin after the detection of coronary artery calcium within a community-based screening cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51(14):1337-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.069.

Korcarz CE, et al. Ultrasound detection of increased carotid intima-media thickness and carotid plaque in an office practice setting: Does it affect physician behavior or patient motivation? J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2008;21:1156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.05.001

Johnson HM, et al. Effects of an office-based carotid ultrasound screening intervention. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24(7):738-47. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.02.013.

Rodondi N, et al. Impact of Carotid Plaque Screening on Smoking Cessation and Other Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(4):344–352. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1326

O’Malley PG, et al. Impact of Electron Beam Tomography, With or Without Case Management, on Motivation, Behavioral Change, and Cardiovascular Risk Profile: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2003;289(17):2215–2223. doi:10.1001/jama.289.17.2215

Rozanski, A, et al. Impact of Coronary Artery Calcium Scanning on Coronary Risk Factors and Downstream Testing: The EISNER (Early Identification of Subclinical Atherosclerosis by Noninvasive Imaging Research) Prospective Randomized Trial. JACC 2011; 57 (15) 1622–1632.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.019

Lederman J, et al. Information given to postmenopausal women on coronary computed tomography may influence cardiac risk reduction efforts. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(4):389-96. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.07.010.

Wood DA, et al. . Nurse-coordinated multidisciplinary, family-based cardiovascular disease prevention programme (EUROACTION) for patients with coronary heart disease and asymptomatic individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease: a paired, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371(9629):1999-2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60868-5.

O’Malley PG. On motivating patients: a picture, even if worth a thousand words, is not enough. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(4):309-10. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1948.